Commodity Markets in turmoil

- Simon Kiwek

- 21. Jan. 2025

- 9 Min. Lesezeit

Aktualisiert: 12. Jan.

Energy, Fertilizers, and Metals: Adaptability Determines the Course of Commodity Prices

Commodities are much like the circulatory system of the global economy. Mines, sources, and farms reliably and steadily pump metals, energy, and agricultural products into the organism of the global economy. They have long been considered a stabilizing factor when crises shook the world. However, with COVID-19, war, and inflation, this rock in the surf was suddenly torn from its foundation, and commodity prices shot uncontrollably in all directions like snapped ropes in a storm. New challenges such as the increasingly critical issue of climate change require not only commodities in rough quantities but also new categories as the era of fossil resources of an old industrial society seemingly comes to an end.

In numbers: The World Bank expects a decrease of about five percent in aggregated commodity prices by 2025 and a further two percent in 2026. This continues a trend from 2024, led by falling oil prices. Yet, despite a fragile ceasefire between Hamas and Israel, the risk of escalation in the Middle East remains, which could invalidate the forecasts. While metal and agricultural commodities should remain stable, rising gas prices may counteract the trend of falling commodity prices. However, above all, other risks loom: China's government is attempting to trigger a consumption boost in its faltering economy with additional fiscal stimuli. Also, the US economy is growing stronger than current trends would suggest. Moreover, high oil prices in past years have led to a diversification of the energy supply, which is imperative in the face of impending climate change.

Global Shocks Ushered in the 2020s

Within weeks of the outbreak of the Corona pandemic, governments put the world into a deep sleep. The global economy came to a halt, and commodity prices plummeted as the factories that processed them shut down. But as soon as the situation stabilized, the economy bounced back faster than expected. Many services such as restaurants and tourism remained closed to people, causing them to shift their spending to goods. Like after a cardiac arrest, the sources had to work even faster to pump commodities into the circulation to supply all organs with blood. Like an excessively high pulse, commodity prices also soared.

Just when this seemed to be over, Russia marched into Ukraine. Both countries are among the largest exporters of commodities. Prices for energy, grain, and fertilizers exploded again. At the same time, the trade war between China and the USA escalated significantly. Between the world's largest economic blocs, there was a fierce exchange of mutual sanctions and trade restrictions. The supply chains, which run through the world economy like blood vessels, were disrupted and blocked. They had to find new paths before they could transport commodities to where they were needed again.

In particular, Europe came into the Kremlin's sights. Natural gas prices and the fear of a supply failure paralyzed the continent. But globally, inflation reached historic highs. Central banks were forced to raise interest rates, which also made investments in the exploration of new commodity sources more expensive. Especially developing countries suffered from food crises due to expensive food. The wildly fluctuating prices tore apart a globalized world that was just beginning to connect more closely. Supply and demand danced wildly past each other. This indicates overall long-term changes: entire sectors and economic blocs are decoupling from each other. Trade wars over scarce resources and control of technologies rage on. At the same time, climate change intensifies extreme weather events.

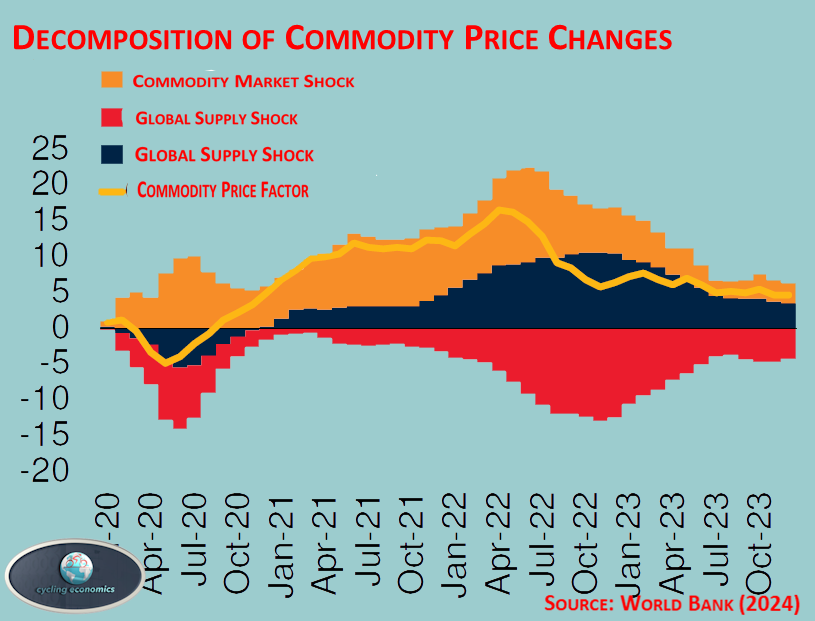

Source 1 Disaggregation des Rohstoffpreis Index

In contrast to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, sector-specific shocks and shocks in resource-rich regions played a significant role in driving commodity prices in the 2020s. The collapse of global economic activity due to lockdowns led to a drastic drop in commodity prices between March and August 2020, as both demand and supply virtually collapsed overnight. However, in the third quarter of 2020, the global economy awoke from its slumber, and demand surged. While restaurants and other social services remained closed, people shifted their demand to goods. China responded by ramping up its production capacities. At the same time, other commodity-specific disruptions occurred: OPEC reduced its oil production. In preparation for its invasion, Russia subtly reduced its natural gas supplies to Europe. When the war broke out in 2022, the situation intensified again. Commodity prices soared once more, nullifying the previous stabilization. The war led to widespread trade conflicts: energy, staple foods, and oilseeds became scarce, as both Ukraine and Russia are key exporters in these markets. The global production capacities of other countries were already operating at full capacity and could not replace the losses. China's declining demand due to a faltering economy somewhat eased the situation, especially as globalized supply chains were disrupted by the increasing economic disentanglement between China and the USA, as well as Russia and the entire West. In October 2023, the Gaza War exacerbated uncertainties again. The fear of an expansion to other oil-rich countries of the Middle East triggered panic in the commodity markets, but this was limited—and was followed by another relaxation.

The New Dynamics in Commodity Markets

Energy prices remain the driving force behind developments. The demand for oil is growing slower than ever before, yet it is also showing a level of volatility previously unknown. The Gaza War and further tensions between Israel and Iran in the oil-rich Middle East sent prices on a wild rally. At the same time, OPEC+, which includes Russia, is exerting its monopoly power in the oil markets. Europe is desperately searching for alternatives to Russian energy exports, in the process significantly disrupting the global market for liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Spot markets were emptied for poorer countries, making long-term planned investments in LNG terminals in East Asia unprofitable - a return to CO2-driving coal ensued. At the same time, long-term purchase commitments were avoided, which in turn made investments in LNG terminals by the USA and Canada along their Atlantic coasts unprofitable. Meanwhile, demand is returning to its usual patterns. The USA is redirecting more of its capacities to East Asia (excluding China). Through long-term contracts and higher prices, Asians secure larger contingents of American shale gas. At the same time, the demand for dirty coal is decreasing while renewable energies are gaining ground.

Source 2 US exports of liquefied natural gas

Significantly less LNG is reaching Europe from the USA than at the beginning of the Ukraine war. A larger share is now going to East Asia and the Pacific region (excluding China), as Europe falls behind in competition due to higher prices and transportation costs. (Source: World Bank, 2024)

China's Crisis Impacts Metal Demand

These developments in favor of renewables have direct impacts on the metal markets. Aluminum, copper, nickel, and lithium are essential for renewable energies, power grids, electric vehicles, and batteries. China is currently accelerating the expansion of these technologies significantly and exporting surplus solar panel capacities worldwide. However, China is experiencing stagnation in other areas.

The faltering Chinese construction sector, along with Europe's weakened industrial production, are driving down the prices for steel and iron. Beijing is desperately trying to stimulate demand through economic stimulus programs. Should China succeed, the demand for renewable energies and electric vehicles could rapidly expand, thereby also increasing the demand for the aforementioned metals. At the same time, China is engaged in a tough struggle for access to critical raw materials such as rare earths, without which the energy transition cannot function. Access is unevenly distributed among countries. Although China itself hosts 37 percent of the most important reserves (and contributes 68 percent of the production), its appetite is nearly insatiable.

The availability of these resources remains a political flashpoint. For many resource-rich countries, particularly in Africa, this opens up opportunities, but also risks—the resource curse rears its head. Many Sahel countries in Africa, rich in uranium and gold reserves and also among the world's poorest, risk being crushed between Western and Russian desires. Populous emerging countries like India and Indonesia, on the other hand, play a different role: they are home to a growing middle class moving to cities. Their demand for capital goods and durable consumer goods is rising. In the digital age, this is synonymous with metals and rare earths. They must secure their fair share of the resources. However, their need for food will also increase.

Climate Change Challenges Agricultural Markets

While good harvests of staple foods like wheat were achieved, regional drought periods in North and South America affected corn production. In Asia, floods destroyed rice fields, leading India, one of the largest exporters of the grain, to impose export restrictions. These measures hit other developing countries hard, especially in Africa, which is already suffering from the ongoing war between the grain-exporting giants, Ukraine and Russia.

A green revolution is more urgent than ever. Climate change intensifies extreme weather events and causes significant uncertainties in the markets. Farmers do not know what prices they will get for their crops, leading to strong fluctuations in the markets for agricultural commodities. Affected commodities include not only rice but also coffee and cocoa. In the medium term, the stability of the agricultural markets thus depends on investments in climate-resistant farming methods. While these lead to immediate costs and also carry the risk of misinvestments, they can stabilize future prices for the benefit of all.

However, fertilizers are at the beginning of food supply. They play a key role in agriculture and thus in feeding the world's population. Their production is, however, extraordinarily energy-intensive. Natural gas is a central resource for the production of ammonia, a main component of nitrogen fertilizers. The supply stops of Russian natural gas forced European manufacturers to throttle their production. This led to rising fertilizer prices worldwide.

Since Europeans managed to stabilize their gas supply in 2024, fertilizer prices have continued to fall. Canada and Morocco have also expanded their production capacities to close supply gaps. Nevertheless, many problems are also homemade: Potassium fertilizers from Belarus and Russia are still under sanctions. Brazil, one of the largest buyers, had a hard time finding new suppliers. Simultaneously, China imposed export restrictions on potassium fertilizer, further pressuring the global market.

Fertilizer prices have returned to pre-COVID pandemic levels since the dramatic peaks in 2022. The affordability index for fertilizers describes the ratio of fertilizer prices to the prices at which crops can be sold on global markets. (worldbank.org, 2024)

A World in Transition and a New Mix of Commodities

The commodity markets are at a crossroads. Permanent changes in global demand are leading to a completely new composition of required resources. Countries like Saudi Arabia are already responding to the pressure of change. They are investing their oil revenues in future fields such as the production of green hydrogen. Long-term changes are becoming clearly apparent.

New dependencies are emerging. Resource-rich countries increasingly find themselves forced to choose between competing blocks. Countries with weak governments risk breaking under this pressure. An example is the Congo, whose cobalt reserves could potentially offer a chance for economic uplift. However, geopolitical tensions and external influences could destroy this dream. Adaptability to the new post-fossil era becomes a crucial factor.

Abbildung 4 Illustration of the Evergreen Maersk Blocking the Suez Canal

Hardly anything illustrates the blocked supply chains of the crises of the 2020s like the mishap of the container ship "Ever Given," which blocked Egypt's Suez Canal in 2021. En route from the Chinese port of Yangshan to Rotterdam, the 400-meter-long ship ran aground in one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. As a result, a backlog of at least 369 ships, laden with goods valued at an estimated 9.6 billion US dollars, could no longer pass through the canal. The cargoes included consumer goods for European buyers, operational supplies and inputs for factories, as well as spare parts. Incidents like this once again stalled Europe's supply chains and highlighted the strategic importance of such bottlenecks. (Source: Corona Borealis Studio, 2021)

Despite these challenges, the global commodity markets have shown remarkable resilience. They recovered from the recent strains with astonishing speed, and a collapse was avoided. After the lockdowns in April 2020, commodity prices reached all-time lows. The subsequent recovery overloaded the supply chains, which could not keep up with the greatly increased production volume, leading to a backlog. However, as the bottlenecks gradually eased, Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022 once again thwarted the recovery. This was followed by a trade war that disrupted the supply chains anew. High-tech devices, energy, and food had to suddenly find new trade routes—like a river blocked by a landslide. The trade flows sought the path of least resistance—and began to flow again.

The World Bank, however, observes a new trend: specific shocks affecting individual regions or individual commodity classes are occurring more frequently. In the past, this meant switching to more affordably priced alternatives. But now, prices are synchronizing; they rise and fall together. For consumers, this means fewer opportunities to avoid high prices. At the same time, this also diminishes the impact of monetary policy measures by central banks aimed at curbing inflation. Thus, the globalized market economy is facing a new era in the second half of the 2020s.